|

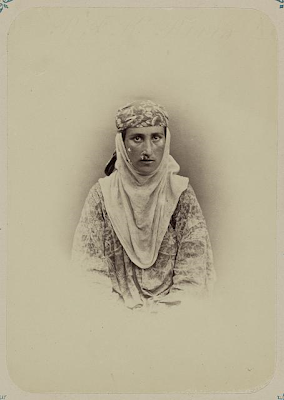

Why so many pictures of Yemenite Jews? (American

Colony Collection, circa 1910) |

In previous features we discussed why the American Colony photographers dedicated so much film to the Yemenite Jews of Jerusalem.Today we present the words of one of the key figures of the American Colony, Bertha Spafford Vester, daughter of the founders of the Colony,

Anne and Horatio Spafford. Bertha took over the management of the American Colony enterprises after her parents' death. She described her life in her fascinating book,

An American Family in the Holy City, 1881-1949. She provided one chapter to the Colony's special relationship with a group of "Gadites" who arrived in 1882. It was believed they were descendants of the tribe of Gad.

CHAPTER TWELVEThe Gadites entered our lives a few months after our arrival in Jerusalem, and until [the 1948] civil war divided Jerusalem into Arab and Jewish zones, with no intercourse between except bullets and bombs, they continued to get help from the American Colony.

|

Yemenite school at Kfar Hashiloach. Yemenite village

in Silwan (Central Zionist Archives, Harvard, circa 1910) |

One afternoon in May 1882 several of the Group, including my parents, went for a walk, and were attracted by a strange-looking company of people camping in the fields. The weather was hot, and they had made shelters from the sun out of odds and ends of cloth, sacking, and bits of matting. Father made inquiries through the help of an interpreter and found that they were Yemenite Jews recently arrived from Arabia.

|

View of Kfar Shiloah in Jerusalem, outside of Jerusalem's

Old City. Note the caves, first homes for Gadite newcomers

(Central Zionist Archives, Harvard, 1898) |

They told Father about their immigration from Yemen and their arrival in Palestine. Suddenly, they said, without warning, a spirit seemed to fall on them and they began to speak about returning to the land of Israel. They were so convinced that this was the right and appointed time to return to Palestine that they sold their property and turned other convertible belongings into cash and started for the Promised Land. They said about five hundred had left Yena in Yemen. Most of them were uneducated in any way except the knowledge of their ancient Hebrew writings, and those, very likely, they recited by rote. As appears, they were simple folk, with little knowledge of the ways of the world outside of Yemen, and that is the same as saying "the days of Abraham."

When they landed in Hedida on the coast of the Red Sea, they were cautioned by Jews not to continue their trip to Jerusalem and that if they did so it would be at peril of their lives. Some of the party were discouraged and returned to Yena. Others were misdirected and were taken to India, The rest went to Aden, where they embarked on a steamer for Jaffa, and came to Jerusalem before the Feast of Passover.

|

Library of Congress caption: "Photograph shows a

Yemenite Jewish man standing in front of Siloan village.

1901 (Source: L. Ben-David, Israel's History - A Picture

a Day website, Sept. 11, 2011)" |

They told about the opposition and unfriendliness they had encountered from the Jerusalem Jews, who, they said, accused them of not being Jews but Arabs. One reason, they said, for their rejection by the Jerusalem Jews was because they feared that these poor immigrants would swell the number of recipients of

halukkah, or prayer money. Early in the seventeenth century, as a result of earthquakes, famine, and persecution, the economic position of the Jews in Palestine became critical, and the Jews of Venice came to their aid. They established a fund "to support the inhabitants of the Holy Land." Later on the Jews of Poland, Bohemia, and Germany offered similar aid. This was the origin of the

halukkah. The money was sent not so much for the purpose of charity as to enable Jewish scholars and students to study and interpret the Scriptures and Jewish holy books and to pray for the Jews in the Diaspora (Dispersion), at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, and in other holy cities of Palestine. The

halukkah, as one could imagine, was soon abused. It only stopped, however, when World War I began in 1914 and no more money came to Palestine for that purpose.

In 1882, when the Yemenites arrived, those who had benefited from the generosity of others were unwilling to pass it on.

Father was interested in the Gadites at once. Their story about their unprovoked conviction that this was the time to return to Palestine coincided with what he felt sure was coming to pass the fulfillment of the prophecy of the return of the Jews to Palestine.

Also, Father was attracted by the classical purity of Semitic features of these Yemenite immigrants, so unlike the Jews he was accustomed to see in Jerusalem or in the United States. These people were distinctive: they had dark skin with dark hair and dark eyes. They wore side curls, according to the

Mosaic law: "Ye shalt not round the corners of your heads, neither shalt thou mar the corners of thy beard." Otherwise their dress was Arabic. They had poise, and their movements were graceful, like those of the Bedouins. They were slender and somewhat undersized. Many of the women were beautiful, and the men, even the young men, looked venerable with their long beards. They regarded as true the tradition that they belonged to the tribe of Gad. They believed that they had not gone into captivity in Babylon, and that they had not returned at the time of Ezra and Nehemiah to rebuild the temple. For thousands of years they had remained in Yemen, hence their purity of race and feature.

The thirty-second chapter of

Numbers tells how the children of Gad and the children of Reuben asked Moses to allow them to remain on the east side of Jordan, which country had "found favor in their sight." It goes on to tell how Moses rebuked them, saying, "Shall your brethren go to war, and shall ye sit here?" Then Moses promised them that if they would go armed and help subdue the country, then "this land shall be your possession before the Lord."

In the thirteenth chapter of

Joshua, "when Joshua was stricken in years," he gives instructions that the Gadites and the Reubenites and half the tribe of Menasseh should receive their inheritance "beyond the Jordan eastward even as Moses the servant of the Lord gave them."

In the

Apology of al Kindy, written at the court of al Mamun, A.D. 830, the author speaks of Medina as being a poor town, mostly inhabitated by Jews. He also speaks of other tribes of Jews, one of which was deported to Syria. Would it be too remote to conjecture that the remnants of these tribes should have wandered to and remained in Yemen? I know there are other theories about how Jews got there, and about their origin, but Father believed that "Blessed be he that enlargeth Gad," and the Group did everything in their power to help these immigrants. We called them Gadites from that time.

|

| Yemenite Jews circa 1900. Why are they near mailbox belonging to the German postal service? (Library of Congress) |

|

Yemenite rabbis, "some of the first immigrants"

(Central Zionist Archives, Harvard) |

They were in dreadful need when we found them.

Some of them had died of exposure and starvation during their long and uncomfortable trip; now malaria, typhoid, and dysentery were doing their work. They had to be helped, and quickly. No time

was lost in getting relief started. The Group rented rooms, and the Gadites were installed in cooler and more sanitary quarters. Medical help was immediately brought. Mr. Steinharf's sister, an Orthodox Jewish woman, was engaged to purchase kosher meat, which, with vegetables and rice or cracked burghal (wheat) she made into a nutritious soup. Bread and soup were distributed once a day to all, with the addition of milk for the children and invalids. One of the American Colony members was always present at distribution time, to see that it was done equitably and well.

|

Translation of the Gadite prayer kept in the Spafford Bible:

Prayer of Jewish Rabbi offered every Sabbath in Gadite synagogue,

June 27?: He who blessed our fathers Abraham, Isaac & Jacob,

bless & guard & keep Horatio Spafford & his household & all that

are joined with him, because he has shown us mercy to us & our

children & little ones. Therefore may the Lord make his days long...(?)

and may the Lord's mercy shelter them. In his and in our days may

Judah be helped (?) and Israel rest peacefully and may the

Redeemer come to Zion, Amen. |

The Gadites had a scribe among them who was a cripple. He could not use his arms and wrote the most beautiful Hebrew, holding a reed pen between his toes. He wrote a prayer for Father and his associates, which was brought one day and presented to Father as a thanksgiving offering. They said that they repeated the prayer daily. I have it in my possession; it is written on a piece of parchment. The translation was made by Mr. Steinhart.

This amicable state of affairs continued for some time. Then the elders, who were the heads of the families, came as a delegation to Father. They filed upstairs to the large upper living room, looking solemn and sad, and smelling strongly of garlic. They told Father that certain Orthodox Jews, the very ones who had turned blind eyes and deaf ears to their entreaties for help when they arrived in such a pitiable state, were now persecuting them under the claim that they were violating the law by eating Christian food. Some of the older men and women had stopped eating, and in consequence were weak and ill. They made Father understand how vital this accusation, even if false, was to them, and they begged him to divide the money spent among them, instead of giving them the food.

Everyone knows how much more economical it is to make a large quantity of soup in one cauldron than in many individual pots; how ever, their request was granted. A bit more money was added to the original sum, and every Friday morning the heads of the Gadite families would appear at the American Colony and be given coins in proportion to the number of individuals to be fed.

They explained to Father that they were trying to learn the trades of the new country and hoped very soon not to need assistance. They had been goldsmiths and silversmiths of a crude sort in Yemen, but Jerusalem at that time had no appreciation or demand for that sort of handicraft. One by one the elders came to tell us they had found work, to thank, us for what we had done, and to say they needed no further help. Father was impressed with the unspoiled integrity of these people.

The Colony continued giving help to the original group of Gadites in decreasing amounts until only a few old people and

widows remained. But these came regularly once a week. Their number was swelled by newcomers and we still shared what we could with them: portions of dry rice, lentils, tea, coffee, and sugar, or other dry articles. After the British occupation of Palestine and the advent of the Zionist organization, with its resources and vast machinery to meet pressing necessities, after forty years our list of dependent Gadites was taken over by them. Even then, individuals continued to come to the doors of the American Colony to ask our help.

One night in June 1948 the American Colony had been under fire all night between the Jews west of us and the Arab legionaries east of us. In the morning a Yemenite Jew lay dead in the road be fore our gates. I recognized Hyam, a Yemenite from the "box colony" near the American Colony. He was one of those who had been receiving help from us for years.

For all this relief work the American Colony was using the money of its members.

The chapter continues with the story of a con-man, Mr. Moses, who stole an ancient scroll from the Yemenites while they were still in Yemen. The Yemenite community in Jerusalem discovered him in Jerusalem and requested that the American Colony help secure the scroll for them.

View comments